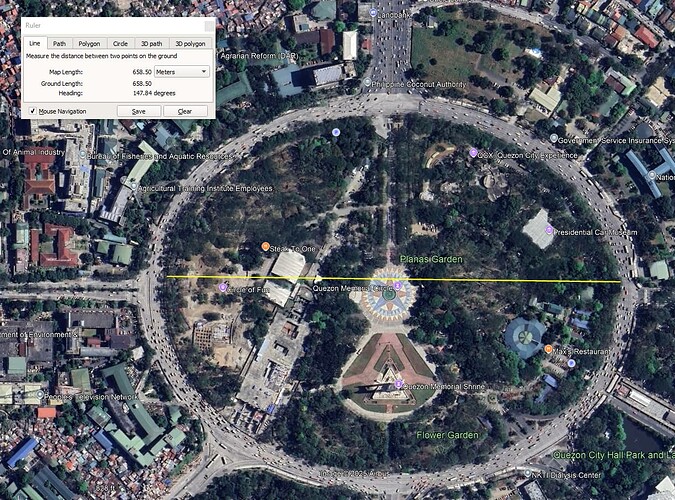

According to the coding manual, “Circular intersections that flow in a single direction around a central island with a radius of 4 meters or more should be coded as ROUNDABOUT.” Based on the attached image, this location meets the criteria and should therefore be coded as a roundabout.

The concern, however, is that coding it as a roundabout may result in a higher safety rating for this section compared to coding it as a series of more than eight 3-leg intersections. This issue is particularly relevant given that the roundabout in question spans approximately 2 kilometers and includes 20 coding segments.

This raises the question: Is there a maximum allowable length for a roundabout beyond which it should no longer be coded as a roundabout, but rather as a regular stretch of road? Or does the current guidance apply regardless of length?

1 Like

Hi Ronnel,

There isn’t a simple answer to this but when you are coding you need to think about the potential crash type and then determine the best attributes to use. Most of the time it’s fairly straight forward, but as your example shows that is not always the case.

At a high level your example might appear to be one big roundabout, but when you look closer at the potential crash locations it’s a bit different. This may have led you to suggest 3-leg intersections, but their crash type is also quite different.

The large roundabout configuration creates a one-way traffic flow past the conflict points, which is quite different to what occurs at a 3-leg intersection, where the most sever crashes occur due to the two-way nature on the adjoining road, where vehicle must cross traffic flows. There appears to be slightly different controls in place at each of the conflict points. For instance, at the intersection of Visayas Ave and Elliptical Road there appears to be a road safety barrier positioned on Elliptical Road that I assume is to try and create a safe merge after the intersection. The problem is because of the poor configuration there is potential for vehicles to travel straight through and into the merge area and so it shouldn’t be coded as a merge. Also, there are locations, such as at Quezon where vehicle can enter at different locations creating the potential for different impact angles.

This highlights a key issue: the conflict points in your example don’t neatly fit any of the intersection types in the iRAP model. In such cases, you need to select the type that best represents the risk profile. If we rule out both ‘Merge’ and ‘Roundabout’ then the next option is a 3-leg intersection, but as mentioned above this is quite different to your situation. One way to address this is by adjusting other intersection-related attributes—such as side road volume and intersection quality—to more accurately reflect the situation. In this case, coding it as a roundabout but with ‘poor intersection quality’ may be the most appropriate solution. The side road volume can have a big impact of the score, so be careful when adjusting is attribute.

Note: If the individual conflict points could be redesigned to fully prevent the straight-through movement mentioned above, that would result in a significant safety improvement.

To answer your last question: if a roundabout is designed to manage speeds effectively and reduce crash angles, it can be coded as a roundabout regardless of its size. That said, current road design standards would typically result in a much smaller roundabout than the one in your example. Also keep in mind that each intersection should only be coded once, even if it extends across multiple coding segments.

1 Like